When the World Stops: Understanding Grief in All Its Forms

- nivsdhadphale

- May 6, 2025

- 6 min read

Understanding Grief Through Psychology, Neuroscience, and in Leadership

Bereavement is one of the most universal aspects of being human. It transcends age, social standing, culture, faith, ethnicity, and gender. They say grief is the price we pay for love, a natural, human response. But what really happens to us when we lose someone? In recent months, several of my friends have experienced profound personal losses, and I’ve found myself transported back to painful chapters in my own life. Quite honestly, the finality of death is frightening - the pain is both unimaginable and confusing. For me, there are gaps - blurred or missing memories, bizarre decisions, unclear timelines and moments that feel like dreams. Blocking out the hurt caused anxiety. Weeping quietly when the opportunity arose was emotionally draining. Reaching out became difficult, and talking about it felt like an insurmountable challenge. The world carrying on as usual felt excruciatingly incomprehensible. Each waking moment was confusing, and the piercing pain was not only emotional, but also physical. The emotional turmoil is difficult to explain. Sadly, people often do not understand the procrastination, the change in personality, or the hypersensitivity that accompanies those of us who are grieving. It is essential to understand grief – since every one of us will experience loss in our lifetime. Yet, no two people grieve in the same way. It is an intensely personal journey.

During some stages of life, grief is more difficult to face, such as for young children who are unable to express their feelings while complex problems can be a direct result of early or sudden bereavement.

But, grief is not only something that follows death. The same or similar feelings may emerge from job loss, divorce, life-changing injuries or illnesses, the end of a project, leaving one’s home country, or transitional events such as menopause. There is no right or wrong way to survive grief. People are often affected depending on the age of the person lost, the circumstances of their passing, and their role in the lives of others. Cultural mourning practices may offer spiritual support and structure during chaos, but once the formalities pass, people are often left with an aching silence.

Eventually, we all hope to find peace and the strength to move forward with acceptance. In this blog I seek only to explain some elements of understanding grief through psychology and neuroscience as well as its effect in our place of work and in leadership. Not everyone needs counselling as close family can support with coping with whichever the loss. The aim of this blog is that understanding and insight might offer some comfort. But you are not alone. Help does exist. If you can find the courage to reach out, reach for a family member, a friend or consult a professional.

Grief Reaction

The normal grief reaction usually follows three stages:

Stage 1 (hours to days) – there is denial which might manifest as numbness with feeling of unreality and incomplete acceptance of the loss.

Stage 2 (few weeks to 6 months) there might be extreme sadness, loneliness, weeping and yearning for the person. During this time anxiety, lack of sleep, lack of appetite is common. Sometimes people feel they could have done more and project their guilt by blaming as they are preoccupied with memories. Physical symptoms and withdrawal are also very common during this time.

Stage 3 – (beyond six months) Gradual acceptance, resumption of normal life, though grief may re-emerge during anniversaries or significant reminders.

When symptoms persist beyond six months (ICD-11) or twelve months (DSM-5-TR), the person may be experiencing Prolonged Grief Disorder, which can affect physical health and daily functioning and might require professional intervention. Sometimes, this can be due to the death being sudden leaving people in a limbo type of state.

The Brain and Body on Grief: What Neuroscience Reveals

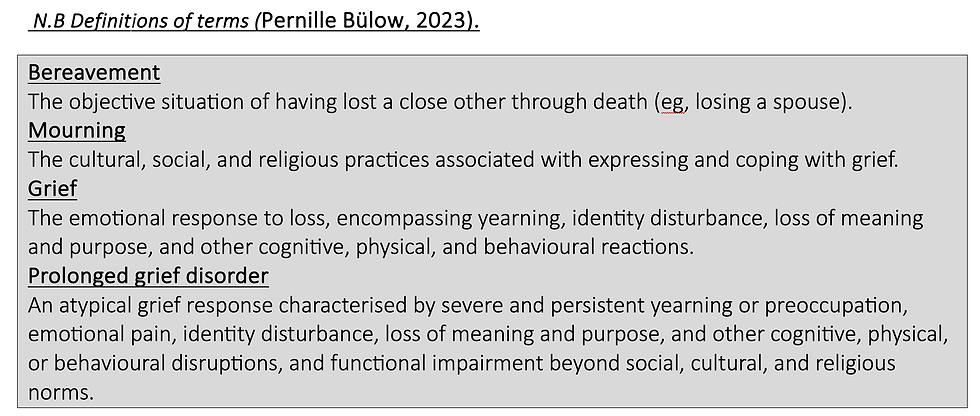

Studies in neuroscience, such as those by Dr Pernille Bülow (2023), show that the grieving brain responds in measurable and consistent ways. Functional MRI scans demonstrate increased activity in the posterior cingulate cortex, which is involved in autobiographical memory and sadness, and decreased activity in the amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which regulate emotional responses and decision-making.

The body also reacts physically to grief. Symptoms can include gastrointestinal distress, fatigue, headaches, autoimmune flare-ups, and cardiovascular problems. Chronic stress related to grief can lead to inflammation and suppressed immunity, increasing the risk of infection. Individuals with anxious attachment styles may even show heightened inflammatory responses. Grief is therefore not just psychological – it is deeply physiological too.

In cases of complicated grief, the nucleus accumbens, which governs the reward pathways, becomes active when the person is reminded of the deceased. This is the same area activated during addiction and forms part of a cycle that intensifies longing and emotional pain. This process makes it harder to move forward.

Psychological Models That Make Sense of Grief

Grief can feel like chaos, unpredictable and sometimes overwhelming while at other times it can feel peaceful and quiet. Scientists have developed models of grief to help us make sense of the emotional terrain – although not for everyone. The models are simply designed to offer reassurance that our feelings are real and have been felt before. Some of these frameworks include:

Kibler and Ross’s Five stages of Grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. The model was designed for terminally ill patients but is widely used to describe grief. The stages do not occur in a sequence, and people tend to jump from one to another or skip some stages.

Worden’s Four Tasks of Mourning is a practical road map. It suggests that those who are grieving should actively accept reality, work through the pain, adjust to life and find a way to find an enduring connection while embarking on a new life.

Dual Process Model ( Stroebe & Schut) suggests that people fluctuate between focusing on the loss and engaging with current life. In other words, people are either focused on the loss by crying, remembering and missing or dedicated to trying to make plans and carry on with life.

Continuing Bonds ( Silverman & Klass) Theory proposes that healthy grief includes keeping the deceased as part of life in memory, rituals, meaning or conversations in our minds.

These models help to normalize grief and show that it is a process of survival, love and adaptation. It is not a failure; it is not madness but something to be experienced in our own unique way to help us move on.

Grief in the Workplace: When Loss Comes to the Office

Grief is automatically associated with death. But in organizational psychology, grief can be due to teams being dissolved, changes in roles, restructuring, or simply long-standing systems being disrupted. In these cases, grief is not always expressed with tears, but with resistance or silence. There is a profound emotional aftermath that can be felt very deeply. In the same way during a personal loss, employees might also rotate between denial, anger, and withdrawal in response to change. This type of anguish in the workplace can cause reduced productivity, fragmentation of team cohesion and overall erosion of morale. In this case the Dual Process Model is useful to understand as employees might move between mourning the old way (resistant to change) or adjusting to the new (resilience). Leaders often expect employees to adapt without acknowledging their loss. As a result, the unresolved organisation grief could manifest as burnout, presenteeism and disengagement.

Empathetic Leadership

It is important for leaders to understand the neuroscience and models of grief. Leaders should be emotionally intelligent so that they recognize grief and offer flexibility to those in transition by listening with compassion. Studies show that social presence, validation can reduce the distress signals in the brain. Employees need someone who is present, attuned and non-judgemental. An effective leader will be empathetic and strategic as it will reduce resistance and foster trust.

Grief Deserves a Place at the Table

Grief is part of our life’s journey. It demands acknowledgement and not avoidance in our personal lives and in our professional roles. It is not something we “get over.” It’s something we learn to live with – and gradually, it becomes part of us in a different way. The intensity may fade, but the memory remains. And that’s okay. With supportive relationships, cultural rituals, empathetic leadership and enough time and space we can not only survive but grow. If you’re going through something right now, know that you’re not alone. There’s not just one right way to grieve. Be kind to yourself. And if someone close to you is grieving, even just being there quietly, and consistently can mean the world.

All of us will encounter grief in our lives. May we meet it with patience, honesty, and peace – for ourselves, and for each other.

Nivs D (Tuesday 6th May 2025)

Further Reading:

Harrison, P.J., Cowen, P., Burns, T. and Fazel, M. (2018). Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. 7th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McCoy, B. (2021). How your brain copes with grief, and why it takes time to heal. NPR. [online] 20 Dec. Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2021/12/20/1056741090/grief-loss-holiday-brain-healing.

O’Connor, M.-F. and Seeley, S.H. (2022). Grieving as a form of learning: Insights from neuroscience applied to grief and loss. Current Opinion in Psychology, [online] 43, pp.317–322. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.019.

Pernille Bülow (2023). The Neuroscience of Grief. Journal of science, humanities and arts, 10(4). doi:https://doi.org/10.17160/josha.10.4.886.

Wolf, C.C. (2024). How the Brain Copes with Grief. [online] Scientific American. Available at: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-the-brain-copes-with-grief/.

Comments